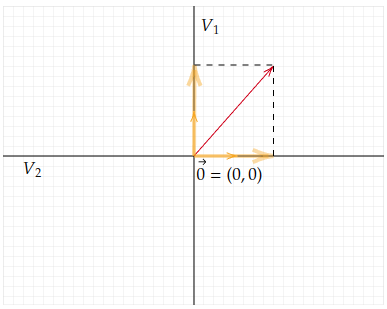

Example. $V_1$ and $V_2$ are subspace of $\mathbb{R}^2$ over $\mathbb{R}$. Any vector (red vector) can be uniquely determine by scalars of vectors in $V_1$ and $V_2$. The intersecion of $V_1$ and $V_2$ is the trivial subspace $\{\vec{0}\}.$

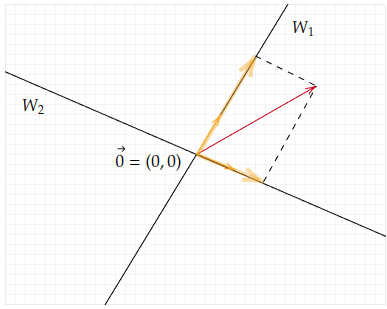

$W_1$ and $W_2$ are another pair of subspace of subspace $\mathbb{R}^2$ over $\mathbb{R}$, which shares the exactly the same properties as $V_1$ and $V_2$.

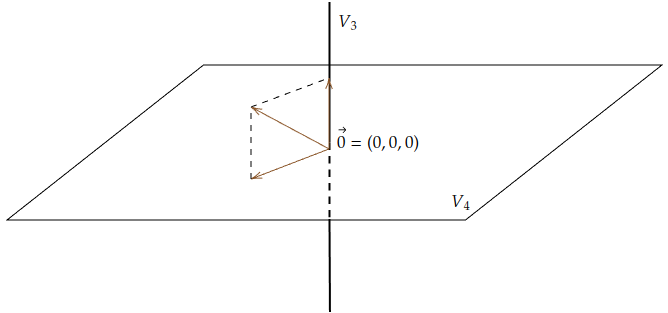

Example. $V_3$ and $V_4$ are subspaces of $\mathbb{R}^3$ over $\mathbb{R}$. Any vector in the space can be uniquely determined by the sum of a vector in $V_3$ and a vector in $V_4$. The intersection of $V_3$ and $V_4$ is the trivial subsapce $\{\vec{0}\}.$

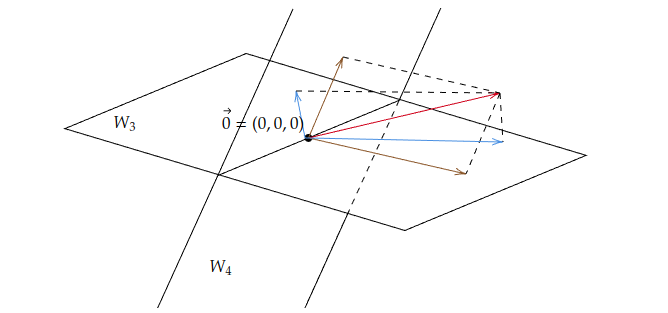

Example. $W_3$ and $W_4$ are subspace of $\mathbb{R}^3$ over $\mathbb{R}$. However, a space vector (represented by the red vector) can be expressed as two different sums of pairs of vectors (blue and brown) from $W_3$ and $W_4$.

Theorem. Any intersection of subspaces of a vector space $V$ is a subspace of $V$.

Introduce the concept of span.

proof. Given two subspace $W_1$ and $W_2$ of $V$, we claim that $W_1\cap W_2$ is a subspace of $V$. We use the first verification theorem:

- The zero vector is clearly in $W_1\cap W_2$ because both $W_1$ and $W_2$ consist the zero vector.

- Let $x,y\in W_1\cap W_2$. Therefore, $x,y\in W_1$. Since $W_1$ is a subspace, $x+y$ is in $W_1$. Similarly, $x+y\in W_2$. Thus, we have $x+y\in W_1\cap W_2$.

- Let $c\in F$. As in the previous argument, we must have $cx\in W_1\cap W_2$.

For an arbitrary number of intersections, we use induction. This is left as an exercise for readers.

Example. Let’s revisit the examples we presented at the beginning:

- $V_1\cap V_2=W_1\cap W_2=\{(0,0)\}$.

- $V_3\cap V_4=\{(0,0,0)\}$.

- $W_3\cap W_4$ is a line passing through the origin.

| Definition. If $S_1$ and $S_2$ are non-empty subsets of a vector space $V$, then the sum of $S_1$ and $S_2$, denoted $S_1+S_2$, is the set $\{x+y | x\in S_1\text{ and }y\in S_2\}.$ The sum of any finite number of non-empty subset$S_1,\ldots,S_n$ of $V$ is defined analogously as the set |

Example. Let’s revisit the examples we presented at the beginning:

- $V_1+V_2=W_1+W_2=\mathbb{R}^2$.

- $V_3+V_4=\mathbb{R}^3$.

- $W_3+W_4=\mathbb{R}^3$.

Theorem. If $W_1$ and $W_2$ are subspace of a vector space $V$ over a field $F$, then $W_1+W_2$ is a subspace of $V$.

proof. We again use the first verification theorem. We may:

- $0=0+0\in W_1+W_2$.

-

Given $v,v^{\prime}\in W_1+W_2$, we have $v=x+y$ ($v^\prime=x^\prime+y^\prime$) for some $x\in W_1$ ($x^\prime\in W_1$ respectively) and $y\in W_2$ ( $y^\prime\in W_2$ respectively). Then, we have

\[\begin{align*} v+v^\prime&=(x+y)+(x^\prime+y^\prime)\\\\ &=(x+x^\prime)+(y+y^\prime)\text{ (by VS2)} \end{align*}\]Therefore, we have $v+v’\in W_1+W_2$.

- Let $c\in F$. Then, we have $cv=c(x+x^\prime)=cx+cx^\prime\in W_1+W_2$.

Let’s focus on $(V_3,V_4)$ and $(W_3,W_4)$. The sum of both pairs is $\mathbb{R}^3$. The key difference is that any vector in $\mathbb{R}^3$ is uniquely determined by vectors in $V_3+V_4$, but it is not the case for $W_3+W_4$. Additionaly, $V_3\cap V_4$ is trivial, while $W_3\cap W_4$ is not. These observations motivate our next definition.

Definition. A vector space $V$ is said to be the direct sum of $W_1$ and $W_2$, denoted by $V=W_1\oplus W_2$, if $W_1$ and $W_2$ are subspace of $V$ such that $W_1\cap W_2=\{0\}$ and $W_1+W_2=V$.

Theorem. Let $W_1$ and $W_2$ be subspaces of a vector space $V$. Then $V$ is the direct sum of $W_1$ and $W_2$ if and only if each element in $V$ can be uniquely written as $x_1+x_2$, where $x_1\in W_1$ and $x_2\in W_2$.

Example. $\mathcal{F}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})=W_1\oplus W_2$ where $W_1$ is the subspace of odd functions, and $W_2$ is the subspace of even functions. For $f\in \mathcal{F}(\mathbb{R},\mathbb{R})$, we define $g=\frac{1}{2}(f(x)+f(-x))$ and $h(x)=\frac{1}{2}(f(x)-f(-x))$

##