Example. The set of degree $2$ polynomials over $\mathbb{R}$

\[P_2(\mathbb{R})=\\{ax^2+bx+c|a,b,c\in\mathbb{R}\\}\]| forms a vector space. We might intuitively think that this vector space is no different from the coordinate system $\mathbb{R}^3=\{(a,b,c) | a,b,c\in\mathbb{R}\}$, just with different notation. The following table illustrates the translation between notations. |

| $\mathbb{R}^3$ | $P_2(\mathbb{R})$ | |

|---|---|---|

| element | $(a,b,c)$ | $ax^2+bx+c$ |

| $x$-axis | $a\cdot(1,0,0)$ | $a\cdot x^2$ |

| $y$-axis | $b\cdot(0,1,0)$ | $b\cdot x$ |

| $z$-axis | $c\cdot(0,0,1)$ | $c\cdot 1$ |

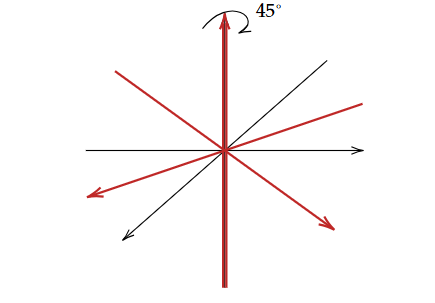

undefined We naturally use the vector $(1,0,0)$ to represent the $x$-axis, and similarly for the other two axes. The set of axes in the table is standard, but it is not the only set we can use. Any three non-parallel lines that pass through the origin can serve as axes. For example, we can rotate the three axises about $z$-axis by 45 degree to create a new grid (see the following figure).

This new set of axes can be represented by $\{(1,1,0),(-1,1,0),(0,0,1)\}$. All of these set, $\{(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)\}$, $\{1,x,x^2\}$, and $\{(1,1,0),(-1,1,0),(0,0,1)\}$, play critical rules in the vector space to which they belong. Adding a vector to these sets would clearly make it redundant. Conversely, removing any vector from these sets would render the sets insufficient to “generate” the entire spaces. They are basic sets in the correspondent vector spaces, so we should call them “basis”.

These concrete examples help us develop similar concepts using axiomatic language. For a set $\beta$ of a vector space to be considered a basis, it must satisfy at least two key properties:

- $\beta$ generates the entire space

- Removing any vector from $\beta$ would render the set insufficient to generate the entire space.

From these two essential properties, we derive the concepts of “span” and “linear independence,” both based on “linear combination.”

Linear Combination and Systems of Linear Equations

Definition. Let $V$ be a vector space and $S$ be a non-empty subset of $V$. A vector $x\in V$ is said to be a linear combination of elements of $S$ if there exist a finite number of elements $y_1,\ldots, y_n$ in $S$ and scalars $a_1,\ldots, a_n$ in $F$ such that $x=a_1y_1+\cdots+a_ny_n$. In this situation it is also customary to say that $x$ is a linear combination of $y_1,\ldots,y_n$.

Remark. We shall use induction to prove that $a_1y_1+\cdots+a_ny_n$ is in $V$.

Theorem. If $S$ is a non-empty subset of a vector space $V$, then the set $W$ consisting of all linear combinations of elements of $S$ is a subspace of $V$. Moreover, $W$ is the smallest subspace of $V$ containing $S$ in the sense that $W$ is a subset of any subspace of $V$ that contains $S$.

proof. (Exercise)

Definition. The subspace $W$ described in Theorem 1.7 is called the span of $S$ (or the subspace generated by the elements of $S$) and is denoted $\text{span}(S)=V$. In this situation, we shall also say that the elements of $S$ generate (or span) $V$.

Example. The vectors $(1,1,0)$, $(1,0,1)$, and $(0,1,1)$ generate $\mathbb{R}^3$